Als DVD & VOD

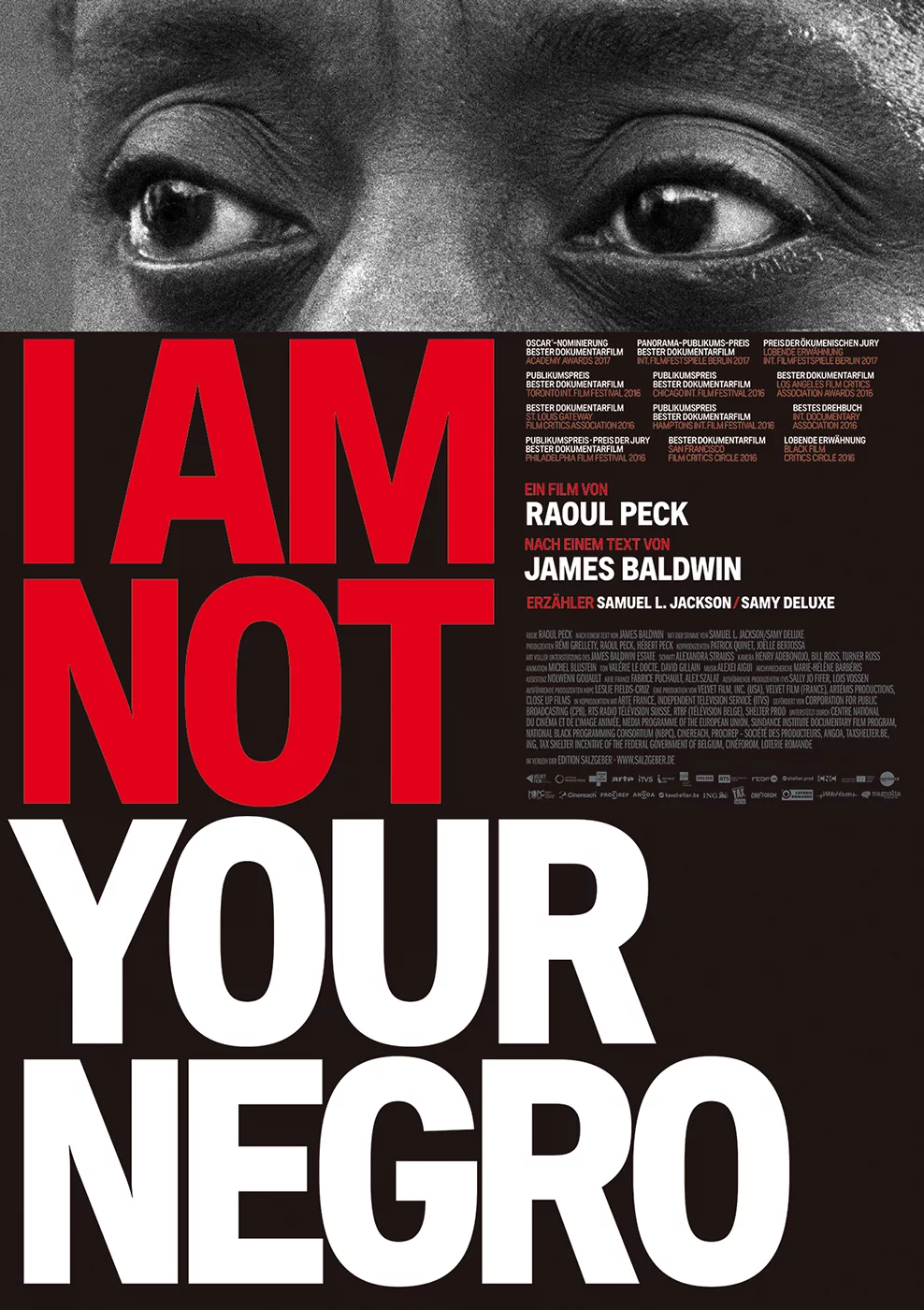

I Am Not Your Negro

ein Film von Raoul Peck

USA / Frankreich / Belgien / Schweiz 2016, 93 Minuten, englische Originalfassung mit deutschen Untertiteln oder deutsche Synchronfassung

FSK 12

Kinostart: 31. März 2017

I Am Not Your Negro

Als der US-Schriftsteller James Baldwin im Dezember 1987 starb, hinterließ er ein 30-seitiges Manuskript mit dem Titel „Remember This House“. Das Buch sollte eine persönliche Auseinandersetzung mit den Biografien dreier enger Freunde werden, die alle bei Attentaten ermordet wurden: Martin Luther King, Malcolm X und Medgar Evers. Die persönlichen Erinnerungen an die drei großen Bürgerrechtler verknüpft Baldwin mit einer Reflektion der eigenen, schmerzhaften Lebenserfahrung als Schwarzer in den USA.

„I Am Not Your Negro“ schreibt Baldwins furioses Fragment im Geiste des Autors filmisch fort und verdichtet es zu einer beißenden Analyse der Repräsentation von Afro-Amerikaner:innen in der US-Kulturgeschichte. Baldwins Worte ertönen über Archivfotos, Filmausschnitte und Nachrichten-Clips der 1950er und 60er Jahre, die noch von Rassentrennung und einer beinah vollkommenen Unsichtbarkeit der Schwarzen in Hollywood geprägt waren; sie erzählen von der Formierung der schwarzen Bürger:innenrechtsbewegung und Baldwins kompliziertem Verhältnis zur Black-Power-Movement. In einer kühnen Erweiterung des literarischen Texts spannt der Film den Bogen bis in die Jetztzeit: zur noch heute gegenwärtigen weißen Polizeigewalt gegen Schwarze, den Rassenunruhen von Ferguson und Dallas und der Black-Lives-Matter-Bewegung.

In einem hochpolitischen Prozess der Aneignung schreibt „I Am Not Your Negro“ damit die US-Geschichte aus einer bis heute unterdrückten Perspektive neu. Der aus Haiti stammende Regisseur Raoul Peck („Lumumba“, 1992/2000; „Der Mann auf dem Quai“, 1993; „Der junge Karl Marx“, 2017) wurde für seinen mitreißenden Dokumentarfilm-Essay auf der Berlinale 2017 mit dem Panorama-Publikums-Preis ausgezeichnet und für den Oscar nominiert.

Trailer

Director’s Statement

Raoul Peck über seinen Film

I started reading James Baldwin when I was a 15-year-old boy searching for rational explanations to the contradictions I was confronting in my already nomadic life, which took me from Haiti to Congo to France to Germany and to the United States of America. Together with Aimée Césaire, Jacques Stéphane Alexis, Richard Wright, Gabriel García Márquez and Alejo Carpentier, James Baldwin was one of the few authors that I could call “my own.” Authors who were speaking of a world I knew, in which I was not just a footnote. They were telling stories describing history and defining structure and human relationships which matched what I was seeing around me. I could relate to them. You always need a Baldwin book by your side.

I came from a country which had a strong idea of itself, which had fought and won against the most powerful army of the world (Napoleon’s) and which had, in a unique historical manner, stopped slavery in its tracks, creating the first successful slave revolution in the history of the world, in 1804.

I am talking about Haiti, the first free country of the Americas. Haitians always knew the real story. And they also knew that the dominant story was not the real story.

The successful Haitian Revolution was ignored by history (as Baldwin would put it: because of the bad niggers we were) because it was imposing a totally different narrative, which would have rendered the dominant slave narrative of the day untenable. The colonial conquests of the late nineteenth century would have been ideologically impossible if deprived of their civilizational justification. And this justification would have no longer been needed if the whole world knew that these “savage” Africans had already annihilated their powerful armies (especially French and British) less than a century ago.

So what the four superpowers of the time did in an unusually peaceful consensus, was to shut down Haiti, the very first black Republic, put it under strict economical embargo and strangle it to its knees into oblivion and poverty.

And then they rewrote the whole story.

Flash forward. I remember my years in New York as a child. A more civilized time, I thought. It was the sixties. In the kitchen of this huge middle-class apartment in the former Jewish neighborhoods of Brooklyn, where we lived with several other families, there was a kind of large oriental rug with effigies of John Kennedy and Martin Luther King hanging on the wall, the two martyrs, both legends of the time.

Except the tapestry was not telling the whole truth. It naively ignored the hierarchy between the two figures, the imbalance of power that existed between them. And thereby it nullified any ability to understand these two parallel stories that had crossed path for a short time, and left in their wake the foggy miasma of misunderstanding.

I grew up in a myth in which I was both enforcer and actor. The myth of a single and unique America. The script was well written, the soundtrack allowed no ambiguity, the actors of this utopia, black or white, were convincing. The production means of this Blockbuster-Hollywood picture were phenomenal. With rare episodic setbacks, the myth was strong, better; the myth was life, was reality. I remember the Kennedys, Bobby and John, Elvis, Ed Sullivan, Jackie Gleason, Dr. Richard Kimble, and Mary Tyler Moore very well. On the other hand, Otis Redding, Paul Robeson, and Willie Mays are only vague reminiscences. Faint stories “tolerated” in my memorial hard disk. Of course there was “Soul Train” on television, but it was much later, and on Saturday morning, where it wouldn’t offend any advertisers.

Medgar Evers died on June 12, 1963.

Malcolm X died on February 21, 1965.

And Martin Luther King Jr. died on April 4, 1968.

In the course of five years, these three men were assassinated.

These three men were black, but it is not the color of their skin that connected them. They fought on quite different battlefields. And quite differently. But in the end, all three were deemed dangerous. They were unveiling the haze of racial confusion.

James Baldwin also saw through the system. And he loved these men. These assassinations broke him down.

He was determined to expose the complex links and similarities among these three individuals. He was going to write about them. He was going to write his ultimate book, Remember This House, about them.

I came upon these three men and their assassination much later. These three facts, these elements of history, from the starting point, the “evidence” you might say, form a deep and intimate personal reflection on my own political and cultural mythology, my own experiences of racism and intellectual violence.

This is exactly the point where I really needed James Baldwin. Baldwin knew how to deconstruct stories. He helped me in connecting the story of a liberated slave in its own nation, Haiti, and the story of modern United States of America and its own painful and bloody legacy of slavery. I could connect the dots.

I looked to the films of Haile Gerima. Of Charles Burnett. These were my elders when I was a youth.

Baldwin gave me a voice, gave me the words, gave me the rhetoric. All I knew through instinct or through experience, Baldwin gave it a name and a shape. I had all the intellectual weapons I needed.

For sure, we will have strong winds against us. The present time of discord and confusion is an unavoidable element. I am not naive to think that the road ahead will be easy or that the attacks will not be at time vicious. My commitment to make sure that this film will not be buried or sideline is uncompromising.

We are in it for the long run. Whatever time and effort it takes.

Pressestimmen/Preise

Pressestimmen

„Ein Dokumentarfilm, der das Leben verändert!“

(Die Zeit)

„Einer der besten Filme, die jemals über die Zeit der Bürgerrechtsbewegungen gedreht wurden!“

(The Guardian)

„Ein Meisterwerk des politischen Kinos!“

(Rolling Stone)

„Ein faszinierender Dokumentarfilm, in dem man mehr über amerikanische Geschichte lernt als in jedem Geschichtsbuch.“

(Titel, Thesen, Temperamente)

Preise/Festivals (Auswahl)

· Nominiert für den Oscar 2017 – Bester Dokumentarfilm

· 67. Int. Filmfestspiele Berlin, Panorama-Publikums-Preis – Bester Dokumentarfilm

· 67. Int. Filmfestspiele Berlin, Preis der ökumenischen Jury – Lobende Erwähnung

· Toronto International Film Festival 2016, Publikumspreis – Bester Dokumentarfilm

· Chicago International Film Festival 2016, Publikumspreis – Bester Dokumentarfilm

· Gotham Awards 2016, Publikumspreis – Bester Dokumentarfilm

· Philadelphia Film Festival 2016, Publikumspreis

· Philadelphia Film Festival 2016, Preis der Jury für den besten Dokumentarfilm

· Hamptons International Film Festival 2016, Publikumspreis – Bester Dokumentarfilm

· Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards 2016, Bester Dokumentarfilm

· Black Film Critics Circle 2016, Lobende Erwähnung

· San Francisco Film Critics Circle 2016, Bester Dokumentarfilm

Credits

Crew

Regie

Raoul Peck

nach einem Text von

James Baldwin

Erzähler

Samuel L. Jackson / Samy Deluxe

Kamera

Henry Adebonojo, Bill Ross, Turner Ross

Schnitt

Alexandra Strauss

Musik

Alexei Aigui

Ton

Valérie Le Docte, David Gillain

Archiv-Recherche

Marie-Hélène Barbéris, Nolwenn Gouault

Produzenten

Rémi Grellety, Raoul Peck, Hébert Peck

Koproduzenten

Patrick Quinet, Joëlle Bertossa

Redaktion ARTE France

Fabrice Puchault, Alex Szalat

Redaktion ITVS

Sally Jo Fifer, Lois Vossen

Redaktion NBPC

Leslie Fields-Cruz

eine Produktion von Velvet Film, Inc. (USA), Velvet Film (France), Artémis Productions und Close Up Films

in Koproduktion mit Arte France und, Independent Television Service (ITVS)

gefördert von Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), RTS Radio Télévision Suisse, RTBF (Télévision belge) und Shelter Prod

mit Unterstützung von Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, MEDIA Programme of the European Union, Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program, National Black Programming Consortium (NBPC), Cinereach, PROCIREP – Société des Producteurs, ANGOA, Taxshelter.be, ING, Tax Shelter Incentive of the Federal Government of Belgium, Cinéforom und Loterie Romande

mit Unterstützung des James Baldwin Estate

im Verleih von Salzgeber